Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Have you ever picked up a business book looking for ideas, or inspiration, or even guidance?

Have you ever picked up a business book looking for ideas, or inspiration, or even guidance?

Books like Pour Your Heart Into It by Howard Shultz or Creativity, Inc. by Ed Catmull—both fantastic books by the way—are all about the smart decisions that helped ceate massively successful businesses worth billions of dollars.

Who doesn’t want to learn from those guys and share in their success?

But what if their success was less about what they did right, and more about being lucky?

Should we question celebrated best-sellers like Good to Great by Jim Collins, which compares two sets of similar companies to extrapolate why one is successful and the other isn’t?

He puts together a list of reasons: level 5 leadership, getting the right people on the bus, chasing big hairy audacious goals—all good ideas that entrepreneurs have tried to emulate for years.

But some entrepreneurs who follow all of this advice still fail.

They have their BHAGs, their hedgehog concepts, and the right team. And still their business doesn’t take off.

Or they do everything recommended in Nail It, Then Scale It, but can’t get traction.

They have great products that solve real market problems and still fail.

As I read Catmull’s Creativity, Inc., I kept thinking about how lucky Pixar was that everything just went right—even when things went wrong. (To be fair, I think Ed Catmull would acknowledge they were indeed very lucky at times). Steve Jobs comes in at just the right time to buy the company. Someone just happened to download an entire movie to an offsite hard drive before the onsite server is erased. Disney wants to renegotiate a contract at a time when Pixar has maximum negotiating power. And on and on.

As I read Catmull’s Creativity, Inc., I kept thinking about how lucky Pixar was that everything just went right—even when things went wrong. (To be fair, I think Ed Catmull would acknowledge they were indeed very lucky at times). Steve Jobs comes in at just the right time to buy the company. Someone just happened to download an entire movie to an offsite hard drive before the onsite server is erased. Disney wants to renegotiate a contract at a time when Pixar has maximum negotiating power. And on and on.

While there’s a lot of great advice and thinking in all of these books, I’m not sure how much of it is repeatable.

Michael Dell is famous for starting his computer business in his dorm room, but he wasn’t the only college student that did that. He is just the one we know about.

Herb Kelleher is famous for Southwest Airlines’ maverick attitude, low-prices, and quick turns at the gate. But they’re not the only airline that did those things. In fact, they took some of their ideas from their competitors. But Southwest gets the press.

Tom Monaghan wasn’t the only guy to deliver food in the 70s. Did he get lucky connecting with the right advertising agency? Or with a product perfect for a market shifting away from home cooked meals to pick-up options? Or something else?

There were thousands of would-be entrepreneurs who had ideas similar to these incredibly successful entrepreneurs. But we don’t hear about the failures, because they were unlucky—and bad luck doesn’t make a great story.

What makes these guys stand out is that they survived the startup journey. They’re the ones who get profiled in the books and magazines. The very thin right edge of the bell curve. They speak at conferences and commencements and appear on CNBC to talk about their success.

But their experience isn’t typical.

It’s not even probable.

What’s worse, even their bad decisions start to look brilliant after things have worked out. If you could go back and watch successful founders at the startup phase of their companies like Sergey Brin at Google, or Marc Benioff at Salesforce, or Ray Kroc at McDonald’s, you’d find that their success wasn’t predictable. There were moments when things didn’t go well and failure was possible or even almost certain. (If this weren’t true, we’d all be able to spot the next great business success, buy up all the stock, and retire to our private islands.)

All of this isn’t to say that startup success is totally random. It’s not. Money, connections, skill sets, timing, and the ability to spot opportunity all play a part. But it just might be that the biggest contributor to success is luck.

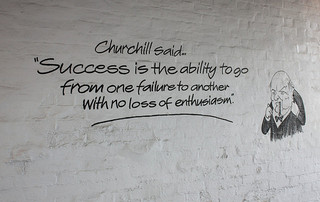

David McRaney, the author of You Are Now Less Dumb, wrote about this topic and concluded the following:

If you spend your life only learning from survivors, buying books about successful people and poring over the history of companies that shook the planet, your knowledge of the world will be strongly biased and enormously incomplete. As best I can tell, here is the trick: When looking for advice, you should look for what not to do, for what is missing… but don’t expect to find it among the quotes and biographical records of people whose signals rose above the noise. They may have no idea how or if they lucked up.

Sounds about right.